Public transportation is the lifeblood of a healthy city, easing congestion, reducing emissions, and ensuring equitable access to jobs, education, and services. While factors like fare prices and service frequency are often cited as key to attracting riders, the most fundamental driver of public transport use lies in the very design of our cities. Urban planning, through its decisions on land use, density, and infrastructure, creates the blueprint that either encourages or discourages public transportation ridership.

Density: The Foundation of a Viable Transit System

The most critical factor in the success of public transportation is population and employment density. A bus or a train is a mass-transit vehicle, and it can only be economically viable and efficient if there are enough people to fill it. In a sprawling, low-density city where homes are far from workplaces and amenities, providing frequent and convenient transit service is nearly impossible. Long, winding routes become necessary to serve a scattered population, increasing travel times and making public transit an unattractive alternative to the private car.

Conversely, high-density development, particularly around transit hubs, creates a natural customer base for public transportation. When residential, commercial, and retail spaces are clustered, travel distances are shortened, and it becomes more feasible for transit agencies to offer frequent and direct service.

Transit-Oriented Development (TOD): A Symbiotic Relationship

Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) is a prime example of urban planning’s direct impact on ridership. TOD is a strategic approach to urban design that maximizes residential, business, and leisure space within a short walking distance of a public transit station. It’s a symbiotic relationship: the transit system makes the development more desirable, and the development’s high-density, mixed-use nature feeds ridership to the transit system.

Key features of successful TOD that boost ridership include:

- Mixed-Use Zoning: By integrating residential, commercial, and retail uses in the same area, TOD reduces the need for long-distance travel. People can live, work, and shop in the same neighborhood, making walking, cycling, or a short transit trip for a purpose-driven journey the most convenient option.

- Walkability and Connectivity: TODs are designed to be highly walkable. This means smaller block sizes, well-lit sidewalks, and a reduction in the space dedicated to automobiles. By prioritizing pedestrians and cyclists, TODs solve the “last mile” problem, making it easy and safe for people to get to and from a transit stop.

- Strategic Parking Policies: Limiting the availability of free parking and introducing parking fees at destinations can be a powerful incentive for people to choose public transit. When the convenience and cost of driving are reduced, the competitiveness of public transportation increases.

Street Design and Car-Centric Policies

Beyond land use, the design of a city’s streets plays a critical role. For decades, many cities have been planned with a “car-first” mentality, leading to wide roads, multiple lanes, and high-speed limits. This design encourages car dependency and makes walking and cycling feel unsafe or impractical.

In contrast, urban planning that prioritizes public transit, walking, and cycling has a direct positive effect on ridership. This can include:

- Dedicated Bus and Tram Lanes: By giving buses and trams their own dedicated lanes, cities can make public transit faster and more reliable than driving a car through traffic. This also serves as a visual reminder of the city’s commitment to public transportation.

- Traffic Calming Measures: Narrowing streets, adding speed bumps, and implementing traffic circles slow down vehicular traffic, making streets safer and more comfortable for pedestrians and cyclists who are on their way to a transit stop.

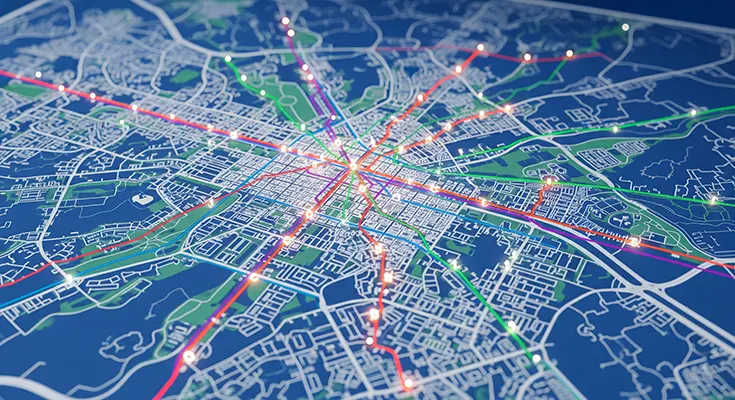

- Integrated Networks: A well-planned transit network connects different modes of transport—buses, trains, subways, and trams—seamlessly. Integrated fare systems and clear signage make it easy for riders to transfer between services, improving the overall user experience and making public transit a viable alternative for complex journeys.

In conclusion, while the quality and affordability of a public transportation system are vital, urban planning is the silent, behind-the-scenes force that truly determines its success. By creating dense, mixed-use communities, designing streets for people, not just cars, and strategically integrating transit with the urban fabric, cities can build environments where public transportation is not just an option, but the preferred choice for a majority of their residents.